Student Debt and Homeownership: Understanding the Trade-Offs in the Modern Economy

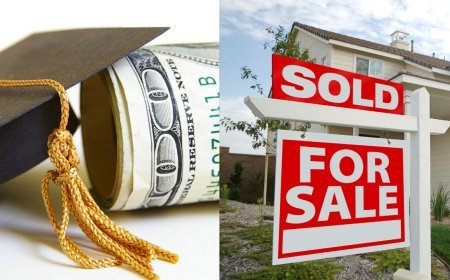

The aspiration of homeownership has long stood as a cornerstone of the American Dream, a tangible symbol of stability, financial success, and wealth accumulation. Yet, for millions of young adults and recent graduates in the modern economy, this dream is increasingly being deferred, overshadowed by a colossal and growing shadow: student loan debt. The United States now grapples with a total outstanding student loan balance that has soared into the trillions, surpassing both credit card and auto loan debt. This monumental financial obligation, taken on in pursuit of education and greater economic opportunity, has become an undeniable drag on the financial lives of borrowers, particularly impacting their ability to achieve key life milestones, chief among them, purchasing a home.

The decision to invest in higher education—an essential step for career advancement and higher lifetime earnings—now comes with a significant trade-off. While a college degree generally increases the probability of employment and greater income, the cost of that education, largely financed through debt, directly conflicts with the foundational requirements for securing a mortgage: accumulating a down payment and meeting stringent debt-to-income (DTI) ratio requirements. The economic narrative of the past two decades is one where the promise of a diploma is perpetually weighed against the burden of its cost.

In This Article:

-

The Rising Tide of Student Debt: An examination of the dramatic increase in education costs and resulting debt burdens.

-

The Homeownership Hurdle: Down Payments and Savings: How monthly loan payments siphon funds away from crucial upfront homebuying costs.

-

The Mortgage Qualification Conundrum: Analyzing the impact of student debt on Debt-to-Income (DTI) ratios and credit scores.

-

The Paradox of Education: The competing forces of increased earning potential versus immediate debt burden.

-

Generational and Racial Disparities: Exploring how the student debt crisis disproportionately affects certain demographic groups.

-

Economic and Societal Ripple Effects: Understanding the broader consequences of delayed homeownership on the economy.

-

Mitigation Strategies and Policy Solutions: Practical advice for borrowers and policy considerations for systemic change.

The Rising Tide of Student Debt

The sheer scale of outstanding student loan debt in the United States is staggering, having more than doubled over the last decade and a half. This exponential growth isn't simply a matter of more people attending college; it reflects a systemic shift in how higher education is funded. State and federal funding to public institutions has lagged, forcing universities to hike tuition, and students have increasingly been left to bridge the gap with private and federal loans.

The average debt per borrower has reached tens of thousands of dollars, fundamentally altering the financial landscape for college graduates. This debt isn't just a number; it translates into significant monthly payments—payments that must be made before a graduate can even begin to save meaningfully for other major life investments. The economic reality is that for a substantial portion of the population, a significant chunk of post-graduation income is immediately dedicated to servicing this educational debt, effectively postponing financial fluidity and the ability to build wealth.

The Homeownership Hurdle: Down Payments and Savings

The most immediate and obvious way student debt thwarts homeownership is by decimating a borrower's ability to save for a down payment. Purchasing a home, particularly for first-time buyers, requires a substantial upfront capital outlay. Even with a modest down payment requirement of 3-5%, the sum is significant, and closing costs add thousands more.

For a recent graduate, a monthly student loan payment, which can often rival or exceed a typical car payment or even a low-end rent payment, acts as a continuous siphon on disposable income. Every dollar allocated to loan repayment is a dollar that cannot be directed into a savings account for a future home. Surveys consistently show that over half of non-homeowning millennials cite student loan debt as a major factor delaying their ability to save enough for a down payment. Econometric models have even quantified this effect, estimating that for every $1,000 increase in student loan debt, the homeownership rate for recent college graduates declines by a measurable percentage. This financial drag can delay homeownership for years, placing young borrowers at a significant disadvantage in a housing market characterized by rapidly appreciating home prices.

The Mortgage Qualification Conundrum

Beyond savings, student debt complicates the home-buying process by creating major hurdles in mortgage qualification. Lenders assess a borrower’s financial health using key metrics, the most critical of which is the Debt-to-Income (DTI) ratio.

The DTI ratio is the percentage of a borrower's gross monthly income that goes toward monthly debt payments, including the future mortgage payment. Lenders typically prefer a DTI ratio of 43% or less, though this can vary by loan type. Student loan payments, whether federal or private, are calculated as part of this total monthly debt. When a significant portion of a borrower's income is already committed to student loan payments, the remaining capacity for a mortgage payment shrinks drastically. A high DTI means the lender must either deny the application or approve a much smaller loan amount, effectively restricting the borrower to lower-priced homes or less desirable markets.

Furthermore, a borrower’s credit score is paramount in determining mortgage eligibility and the interest rate offered. While responsibly managing student loans can positively contribute to a credit history, any delinquency or default due to financial strain can severely damage a credit score. Given the high balance and long repayment terms of student loans, a single misstep can have a prolonged negative impact, potentially disqualifying a borrower from the best mortgage rates and sometimes from homeownership altogether. Lenders often have specific, and sometimes conservative, rules for calculating the monthly payment to use for DTI if a student loan is in deferment or on an income-driven repayment (IDR) plan with a $0 payment, which can still artificially inflate a borrower’s perceived monthly debt obligation.

The Paradox of Education

The irony at the heart of the student debt crisis is the paradox of education. Higher education is supposed to be the escalator to a better financial life, providing the human capital necessary for higher lifetime earnings. Statistically, college graduates earn significantly more over their careers than those with only a high school diploma. This increased earning potential is the very mechanism that should, in theory, accelerate their path to homeownership.

However, the dramatic inflation of tuition costs has meant that the short-term financial burden of debt often outweighs the immediate financial benefit of the degree. The wealth premium associated with higher education has declined for many, as the increasing cost of college, financed with rising student debt, eats away at net wealth. For individuals who take on significant debt but do not complete their degree—a scenario with lower earning potential—the financial consequences are most severe. They carry the debt burden without the corresponding boost in income, making homeownership a near-impossible aspiration.

The trade-off becomes a complicated calculation: accept immediate financial hardship for long-term gain, or forego the degree and potentially face a lifetime of lower earnings. For a growing number of graduates, the long-term payoff is simply delayed, pushing back the timeline for achieving milestones like homeownership, marriage, and starting a family.

Generational and Racial Disparities

The impact of student debt on homeownership is not felt equally across the population; it deepens existing generational and racial disparities in wealth accumulation.

Millennials and Generation Z are bearing the brunt of the debt crisis, graduating into a labor market where wages have struggled to keep pace with both tuition inflation and skyrocketing housing costs. They face a unique economic squeeze that their parents' generation did not. For a significant majority of non-homeowning millennials, student debt is the primary culprit delaying their ability to buy.

The disparity is particularly stark among racial and ethnic groups. Black and Hispanic borrowers are disproportionately affected. Black students, on average, borrow more for college and have higher debt levels than their white counterparts, even when controlling for degree level, largely due to systemic lack of intergenerational wealth. Less access to familial wealth means they are less likely to receive financial help for tuition or a down payment, making them more reliant on loans and thus more susceptible to the debt-to-homeownership trade-off. Research has shown that homeownership rates among young Black college graduates are significantly lower than those of young white adults who did not even complete high school, illustrating how student debt compounds pre-existing structural inequalities to widen the racial wealth gap.

Economic and Societal Ripple Effects

The delay of homeownership due to student debt is not merely an individual financial problem; it has far-reaching economic and societal ripple effects.

Reduced Consumer Spending: High student loan payments reduce a consumer's disposable income, leading to decreased spending on goods and services. This reduction in consumption acts as a persistent drag on local and national economic growth.

Impact on the Housing Market: A large segment of potential first-time homebuyers being sidelined dampens demand, particularly for entry-level homes. While this may slightly cool down certain markets, it also contributes to a lack of housing inventory mobility, as existing homeowners are unable to move up without a buyer for their starter home. It also hinders the wealth-building potential of homeownership, which is historically the primary vehicle for middle-class wealth accumulation in the United States. Delayed homeownership means delayed equity accumulation, which translates to less generational wealth to pass on.

Delayed Life Milestones: The financial pressure from student debt is linked to delays in other major life events, including marriage, having children, and even starting a small business. This collective delay of foundational life decisions can have long-term consequences for economic vitality and social cohesion.

Mitigation Strategies and Policy Solutions

Addressing the student debt-to-homeownership trade-off requires a multi-faceted approach involving both individual strategies and systemic policy reforms.

Strategies for Borrowers:

-

Prioritize High-Interest Debt: Borrowers should focus on paying down high-interest student loans aggressively to free up cash flow sooner.

-

Utilize Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) Plans: Federal student loan borrowers can enroll in IDR plans, which cap monthly payments based on income and family size. A lower payment can significantly improve the DTI ratio for mortgage qualification, though it may extend the total repayment time.

-

Explore Down Payment Assistance (DPA) Programs: Many states and local governments offer DPA programs, some of which are specifically tailored to help borrowers with student loan debt. Programs that provide grants or forgivable loans for down payment and closing costs can bridge the crucial savings gap.

-

Boost Your Credit Score: Maintaining timely payments on all debts and keeping credit utilization low will maximize a borrower's credit score, which is critical for securing a favorable mortgage interest rate.

Policy Solutions:

-

Tackle College Affordability: The most direct solution is to reduce the need for borrowing. This includes increasing state and federal funding for public colleges and universities to reduce tuition reliance, and expanding grant aid.

-

Reform Mortgage Underwriting: Lenders and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) should continue to refine mortgage underwriting standards to better account for the flexibility of IDR plans. Some reforms have already begun, allowing lenders to use the actual IDR payment (even a $0 payment) rather than a percentage of the total loan balance for DTI calculation, which can significantly improve a borrower's qualification chances.

-

Targeted Loan Repayment Assistance: Implement or expand state programs that offer student loan repayment assistance in exchange for purchasing a home in a specific area, such as the SmartBuy programs being tested in some states.

-

Address Racial Equity: Policy must specifically address the disproportionate debt burden on minority borrowers through targeted loan forgiveness, grants, and wealth-building initiatives that rectify historical inequities.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the American Dream

The collision of escalating student debt and rising housing costs has created a profound economic barrier, redefining the achievable milestones for an entire generation. What was once a reliable path—college, career, and homeownership—is now a perilous financial tightrope walk.

The challenge ahead is to re-establish the traditional value proposition of a college degree: a clear and unobstructed pathway to greater financial security and the capacity to build wealth. While education remains a vital investment in human capital, the cost structure must be rebalanced. Until then, the trade-off between educational debt and the American Dream of homeownership will continue to exert a powerful, and often negative, influence on the trajectory of the modern economy. For policymakers, lenders, and individuals alike, understanding this complex dynamic is the first step toward forging a more prosperous and equitable future where the pursuit of knowledge doesn't necessitate the forfeiture of one's most fundamental financial aspirations.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0